Manifest-free ETW in C++

ETW is a great technology when all the stars line up, but various iterations over time have had various limitations, and it often isn’t the easiest technology to work with.

One of the main challenges previously was the need to ship a manifest with your instrumented code, and installing the manifest when installing the app would often require custom actions and admin privileges for the installer.

With the new TraceLogging framework, “manifest-free” ETW became a thing, and instrumenting and distributing an app become simpler.

The struggle

Recently I was trying to include some ETW events in a project built

with Clang/LLVM. I was attempting to use the “manifest-free” TraceLogging approach,

however the inclusion of the Windows SDK <TraceLoggingProvider.h> header was causing

compile errors in Clang++. (Which may have since been fixed). This led me to try

and decipher what this header was doing exactly, and how to recreate this functionality

just using standard C++.

Note: My project requires using C++14, hence not using some features of C++17 (such

as std::string_view) which could have simplified some of the code below.

My first approach to understanding the TraceLogging header was to repeatedly “Go to definition” on the macros being used and try to decipher them, but this quickly became intractable. There are a lot of non-trivial macros that cross-reference and nest in various ways.

The next approach was to compile a simple use-case outputting the pre-processed

source file to see what this got converted to. This reveals the extent of the

processing these macros do. For example, when using the <TraceLoggingProvider.h>

header, this simple line to log an ETW event:

TraceLoggingWrite(g_hMyComponentProvider, "My1stEvent",

TraceLoggingInt32(42, "MyIntField"),

TraceLoggingString("some values", "MyStrField"));

Got turned into the below by the pre-processor. Note the various uses of __pragma,

__declspec, and __annotation. And even this code still calls into other helper

methods from the header (e.g. the _Tlg* calls):

do {

__pragma(warning(push))

__pragma(warning(disable:4127 4132 6001))

__pragma(warning(error:4047))

__pragma(execution_character_set(push, "UTF-8"))

__pragma(pack(push, 1))

typedef _TlgTagEnc<0> _TlgTagTy;

enum { _TlgLevelConst = 5 };

static struct {

CHAR _TlgBlobTyp;

UCHAR _TlgChannel;

UCHAR _TlgLevel;

UCHAR _TlgOpcode;

ULONGLONG _TlgKeyword;

UINT16 _TlgEvtMetaSize;

_TlgTagTy::type _TlgEvtTags;

char _TlgName[sizeof("My1stEvent")];

char _TlgName0[sizeof("MyIntField")];

INT8 _TlgIn0;

char _TlgName1[sizeof("MyStrField")];

UINT8 _TlgIn1;

}

__declspec(allocate(".rdata$zETW1"))

__declspec(align(1))

const _TlgEvent = {

_TlgBlobEvent3,

11,

_TlgLevelConst,

0,

0,

sizeof(_TlgEvent) - 11 - 1,

_TlgTagTy::value,

("My1stEvent"),

("MyIntField"),

TlgInINT32,

("MyStrField"),

TlgInANSISTRING

};

TraceLoggingHProvider const _TlgProv = (g_hMyComponentProvider);

if ((UCHAR)_TlgLevelConst < _TlgProv->LevelPlus1 && _TlgKeywordOn(_TlgProv, _TlgEvent._TlgKeyword)) {

EVENT_DATA_DESCRIPTOR _TlgData[2 + 1 + 1];

UINT32 _TlgIdx = 2;

( _TlgCreateDesc<INT32>(&_TlgData[_TlgIdx], (42)),

_TlgIdx += 1,

_TlgCreateSz(&_TlgData[_TlgIdx], ("some values")),

_TlgIdx += 1,

__pragma(warning(disable:26000)) __annotation(L"_TlgWrite:|" L"23" L"|" L"g_hMyComponentProvider" L"|" L"\"My1stEvent\"" L"=" L"|" L"\"MyIntField\"" L"=" L"|" L"\"MyStrField\"" L"="),

_TlgWrite(_TlgProv, &_TlgEvent._TlgChannel, 0, 0, _TlgIdx, _TlgData)

);

}

__pragma(pack(pop))

__pragma(execution_character_set(pop))

__pragma(warning(pop))

} while (0);

Under the covers

Reverse engineering this further, and stepping through the code, it was surprising

to see how simple everything ultimately is. (Note: I found afterwards that much of this

info is documented in the TraceLoggingProvider.h file - starting at a helpful

line 1804). Basically to log a “manifest-free” ETW event you need to:

- Register the provider as usual, using the Win32 API

EventRegister. - Construct the

EVENT_DESCRIPTORfor the event as usual, though ensure the event is logged to channel 11. (The Id and Version are also less important for manifest-free events). - Construct the

EVENT_DATA_DESCRIPTORarray as usual for the event, prefixed with two additional descriptors:- One to provide the “provider traits” (basically the provider name).

- One to provide the event metadata (i.e. the event & field names and types).

- Call the usual Win32 API to log the event. (e.g.

EventWriteorEventWriteTransfer) - If desired, when done unregister the provider as usual with the Win32

EventUnregisterAPI.

That’s effectively it for simple ETW events (I’m ignoring things like ETW Activities or logging fields containing arrays or custom structs in this write up). Ultimately, just three methods from kernel32.lib are called from user code.

Packing data without pragmas and structs

Constructing the event metadata is where things get tricky. This is the bulk of

the goop in the preprocessor output above, using __pragma(pack(push, 1)) to ensure

fields are tightly packed, and then inline declaring a constant instance of a struct

to describe the event metadata. Modeling this in standard C++ wasn’t trivial. (And

arguably the resulting “template metaprogramming” isn’t easier to read than the macros,

which is unfortunate, but it is standard C++).

To get the metadata as a series of tightly packed bytes at compile-time, I wanted

to use constexpr variables in C++. It turns out to be surprisingly tricky to

take a string literal in C++ (as the event and field names will be represented)

and use them in constexpr functions, especially as being limited to C++ 14 meant

I couldn’t use std::string_view.

To manipulate a string literal in a constexpr function, the best approach I could

find was to reference it as an array of characters of known size (the template parameter

N in the code below). To make it easier to index into the character array, it was

also helpful to have the compiler create an index sequence along with it (idx below), e.g.

template <size_t N, typename idx = std::make_index_sequence<N>>

constexpr auto MakeStrBytes(char const (&s)[N]) {

return str_bytes<N>{s, idx{}};

}

The str_bytes type constructed above is a constexpr value consisting of the

characters of the string. The implementation for this is shown below. A second constructor

is also shown which allows for the joining of two character arrays into a sequence of bytes.

template <size_t N>

struct str_bytes {

template <std::size_t... I>

constexpr str_bytes(char const (&s)[N], std::index_sequence<I...>)

: bytes{s[I]...}, size(N){};

// Concatenate two str_bytes

template <std::size_t s1, std::size_t s2, std::size_t... I1, std::size_t... I2>

constexpr str_bytes(const str_bytes<s1>& b1, std::index_sequence<I1...>,

const str_bytes<s2>& b2, std::index_sequence<I2...>)

: bytes{b1.bytes[I1]..., b2.bytes[I2]...}, size(N) {}

char bytes[N];

size_t size;

};

With this in place, we can not only join strings, but also bytes containing other values. For example, to append a byte indicating the type of the field to the name, I implemented the below function:

// Help function to ease joining instances

template <std::size_t s1, std::size_t s2>

constexpr auto JoinBytes(const str_bytes<s1>& b1, const str_bytes<s2>& b2) {

auto idx1 = std::make_index_sequence<s1>();

auto idx2 = std::make_index_sequence<s2>();

return str_bytes<s1 + s2>{b1, idx1, b2, idx2};

}

// Join a field name with a byte indicating the field type.

template <size_t N>

constexpr auto Field(char const (&s)[N], uint8_t type) {

auto field_name = MakeStrBytes(s);

const char type_arr[1] = {char(type)};

return JoinBytes(field_name, MakeStrBytes(type_arr));

}

There are a few other helper methods to ease constructing the ETW event metadata, as shown

in the source file at https://github.com/billti/cpp-etw/blob/master/etw-metadata.h.

This includes a variadic template function to simply pass along all the fields with the

event name to construct a constexpr byte array of the metadata, for example:

constexpr static auto event_meta = EventMetadata("my1stEvent",

Field("MyIntVal", kTypeInt32),

Field("MyMsg", kTypeAnsiStr),

Field("Address", kTypePointer));

The result of the above is a constant byte array representing the metadata for the event, constructed at compile time.

With constructing the metadata out of the way, the next step is to ease the work needed to implement a provider and log events. Every event requires an event descriptor to describe the event id, level, keywords, etc. Again, this data is static, so a helper method can easily make this a compile-time constant:

// Besides the event id, everything else can default to 0.

constexpr auto EventDescriptor(USHORT id, UCHAR level = 0,

ULONGLONG keyword = 0, UCHAR opcode = 0,

USHORT task = 0) {

return EVENT_DESCRIPTOR{id,

0, // Version

kManifestFreeChannel, // Channel 11

level,

opcode,

task,

keyword};

An ETW base class

The TraceLoggingProvider.h header does provide a callback mechanism to efficiently

track if the provider is enabled, then check this before logging any events. This

can be easily implemented in a base class also, along with registering and unregister

the provider.

An interesting feature of Clang (from GCC) is the builtin that supports indicating

that a condition is likely (or unlikely), named __builtin_expect. This allows for

optimization such as moving code unlikely to be executed to the end of the function.

For example, as the provider will usually NOT be enabled, the check could be written as:

// GCC/Clang supported builtin for branch hints

#if defined(__GNUC__)

#define LIKELY(condition) (__builtin_expect(!!(condition), 1))

#else

#define LIKELY(condition) (condition)

#endif

bool IsEventEnabled(const EVENT_DESCRIPTOR* pEventDesc) {

if (LIKELY(this->is_enabled == false)) return false;

return (pEventDesc->Level <= this->current_level) &&

(pEventDesc->Keyword == 0 ||

((pEventDesc->Keyword & this->current_keywords) != 0));

}

Once various functions are inlined and optimized, this resulted in the below CPU instructions at the location in the user code where the ETW logging call was made. Basically, only 3 additional instructions, and no branch, are executed when logging is not enabled. This can also reduce the number of instructions fetched into the instruction cache during execution, if the code after the main body of the function is never executed.

;; ... code in the function prior to the ETW tracing call

;; Start of check if the provider is enabled

488b05d64f0000 mov rax, qword ptr [mydll!my_provider] ;; Load the provider instance

803801 cmp byte ptr [rax], 1 ;; First byte is the 'enabled' field

0f844f020000 je mydll!sort_array+0x2a3 ;; Jump to the tracing code if enabled

;;... rest of the function body

c3 ret

;; Remaining instructions to do actual tracing are after the mainline code's ret (target of 'je' above)

80784a04 cmp byte ptr [rax+4Ah], 4

0f82a7fdffff jb mydll!sort_array+0x54 (00007ff6`66a71124)

0fb75048 movzx edx, word ptr [rax+48h]

;; ... remaining tracing code, then a jump back to the code after the tracing call

To implement a method to write an event to ETW, derived classes then simply implement

one function for each event to log, and call the base class LogEventData method

to do all the work. e.g.

void MyProvider::Log3Fields(INT32 val, const std::string& msg, void* addr) {

constexpr static auto event_desc = EventDescriptor(100);

constexpr static auto event_meta = EventMetadata("my1stEvent",

Field("MyIntVal", kTypeInt32),

Field("MyMsg", kTypeAnsiStr),

Field("Address", kTypePointer));

LogEventData(&event_desc, &event_meta, val, msg, addr);

}

The LogEventData implementation takes a pointer to the compile-time data representing

the event metadata, and uses a parameter pack to handle the event data, e.g.

template <typename T, typename... Fs>

void LogEventData(const EVENT_DESCRIPTOR* p_event_desc,

T* meta, const Fs&... fields) {

if (!IsEventEnabled(p_event_desc)) return;

const size_t desc_count = sizeof...(fields) + 2;

EVENT_DATA_DESCRIPTOR descriptors[sizeof...(fields) + 2];

// etc.

In general, the provider methods to log events should be as simple as possible,

(for example, like the Log3Fields method shown above), and be inline methods

implemented in the header file, which will allow the compiler to inline the tracing

calls into the instrumented code as shown in the assembly above. (Link time optimization

may also be able to do this, but I didn’t try it).

Performance

I’ve read ETW notes that state that on an average machine a provider should be able to log about 10,000 events/sec without too much overhead. In my simple testing, writing a trivial app to allocate, fill, and sort random arrays (i.e. mostly memory and CPU bound), I noticed on average about a 3% overhead (increase in execution time) with the provider enabled and recording around 10,000 events/sec over a large number of runs. This is on my Surface Book 2, which is a decent laptop, but is still just a laptop.

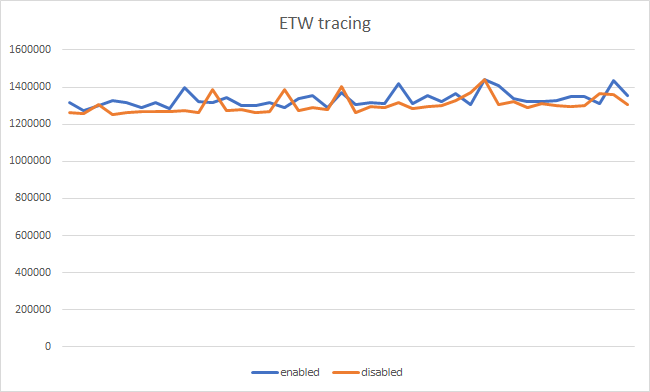

The below charts shows the execution time (in microseconds) over 40 runs with the provider enabled and disabled. The overhead is often less than the noise.

The difference between runs where the provider was disabled, or the provider was completely removed, was not observable. (i.e. Instrumenting the code is effectively free, but you pay a small overhead when a session is actually listening for events).

Sample code

For the complete project demonstrating how to use the C++ only approach to logging manifest-free ETW events, see project on GitHub at https://github.com/billti/cpp-etw.